School-Based Therapy

School-based therapy provides children with disabilities and delays improved access to education and helps each child reach their educational potential. CARE for Children contracts with school districts in McKean and Potter Counties to provide School-based Physical Therapy, Occupational Therapy, and Speech-Language Services. School-based therapy services support students so they can better access school.

The role of the Physical Therapist (PT), the Occupational Therapist (OT), the Occupational Therapy Assistant (COTA) and Speech and Language Pathologist (SLP) is to integrate therapeutic strategies and interventions that coordinate with the student’s curriculum, rather than providing related services as a “special subject” during the school day. Therapy services provide support and adaptations to allow function in the school. School-based therapy services are not curative or rehabilitative in nature.

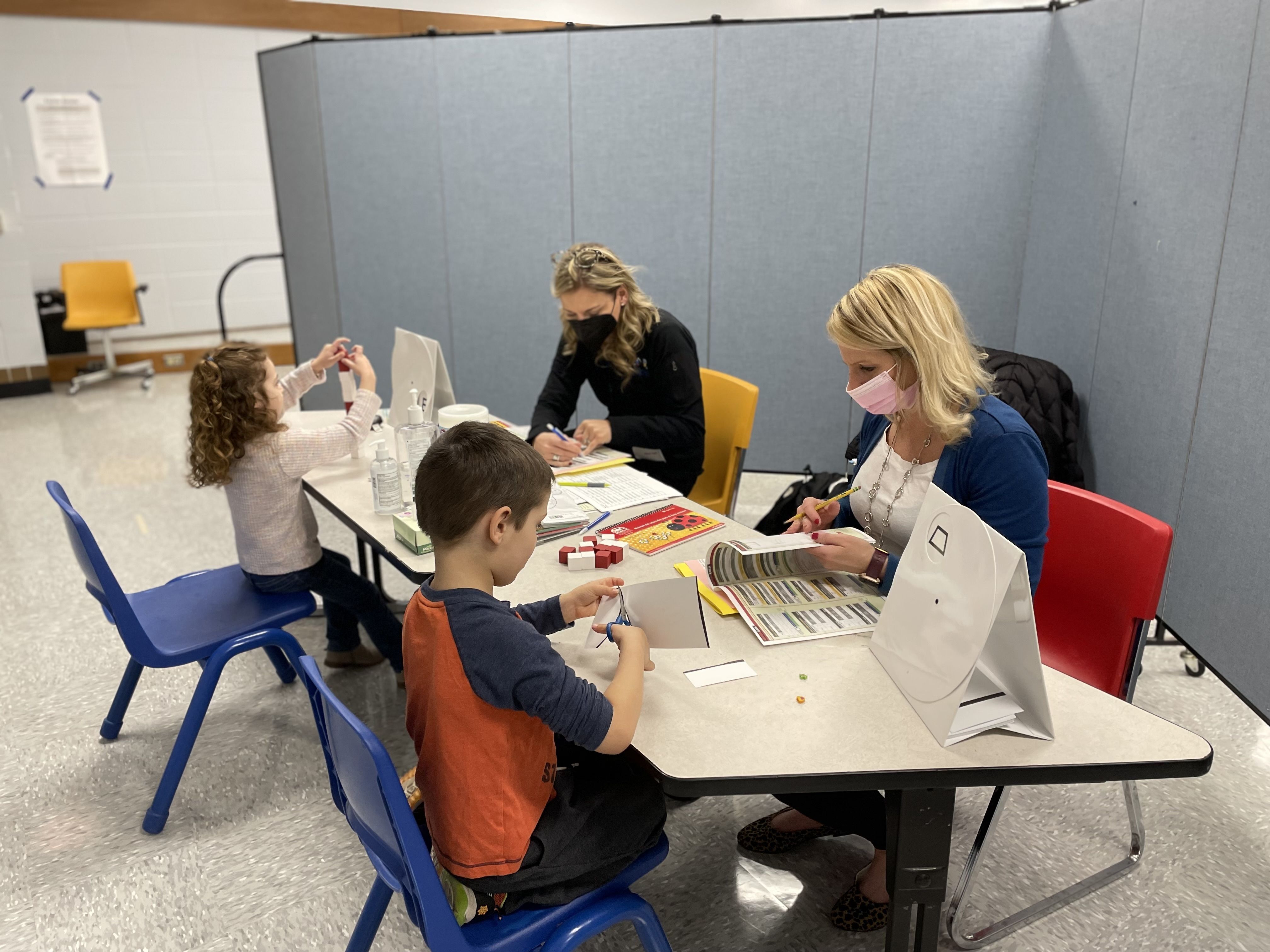

School-based therapy services are a collaboration between educators, therapists, and families. For the student who experiences challenges in school because of a disability, delay, or injury it is essential for everyone to work together and follow through in the classroom, during the therapy session, and at home to meet the child’s educational goals.

Depending on individual needs, a student may only require services for a specific duration. As the student’s ability to participate in the school environment improves and challenges are overcome, the team will determine if services should be less frequent, consultative or discontinued. School Based Physical Therapy, Occupational Therapy, and Speech-Language Services are three of the core services CARE for Children provides in our efforts to “improve the lives of children of all abilities”.

School-Based Physical Therapy

School based physical therapy is provided to assist a child with a disability or delay better access educational opportunities. School-based physical therapy focuses on a child’s ability to safely negotiate the school environment as independently as possible.

Physical therapy interventions are designed to enable the student to travel throughout the school environment; participate in classroom activities; maintain and change positions in the classroom; as well as manage stairs, restrooms; the cafeteria, more fully utilize the playground equipment; and participate in physical education class.

Physical therapists also work with adaptive equipment to assist children with day-to-day tasks.

The school team along with the child’s family work to determine whether a child has a need for special education, and/or requires related services such as physical therapy. A physician’s prescription is needed to start the evaluation process.

School-based therapy is provided to give students improved access to education. It is not a substitute for medically-based therapy.

The role of the Physical Therapist in providing evaluation and treatment in the school setting

The Physical Therapist addresses motor function that prevents a child from accessing his/her education or achieving a goal that has been set by the school team. Special consideration is given to mobility skills that affect the child’s ability to move within or be evacuated from the school building.

Balance and posture are addressed as they relate to the child’s need to interact with teachers, peers and educational materials (e.g. sitting at a desk, standing in a line). PT’s help with adaptive equipment (e.g. wheelchairs, standers, walkers) that the child may need to complete everyday tasks. Physical therapists assist with adapting activities. For example, they may assist in gym class with a child who uses a wheelchair, so the student is able to be included in the activities planned.

Physical Therapists focus on Gross Motor Skills

Gross Motor Skills are large movements of the body, which relate to mobility and active play.

Activities that promote the development of gross motor skills:

- Playground equipment

- Endurance activities

- Swimming

- Ball Toss

- Kick Ball

- Jump Rope, Skipping, galloping, hopping

- Playing outside

- Imitating animals

- Wheelbarrow walking

- “Simon Says”

- Log Rolling

- Riding bicycles

- General exercises

- Walking a line, curb, railroad ties

School-Based Occupational Therapy

CARE occupational therapy staff provide school-based evaluation and treatment for children with physical and developmental disabilities as well as children with delays.

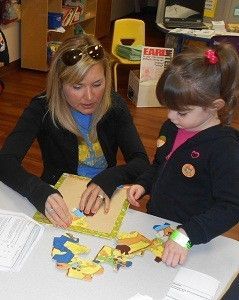

Schools provide occupational therapy when a child with a disability or delay requires this related service to help the student better access his or her education. Occupational therapists use focused activity to promote self-help, fine motor, visual-motor, and written communication skills, and to facilitate a child’s active participation in self-maintenance; academic and vocational pursuits; and play activities that occur in school environments.

Occupational therapists and occupational therapy assistants work to help children accomplish the daily tasks required for success in school, such as writing, painting, playing with toys, and cutting with scissors.

The occupational therapist may adapt, design and fabricate equipment so the student can better function while at school, whether in the classroom, lunchroom, or restroom.

Using direct and indirect services, as well as assistive technology and environmental modifications, school occupational therapists collaborate with parents, teachers and other educational staff to help improve a student’s chance for reaching their full potential.

The school team along with the child’s family work to determine whether a child has a need for special education, and/or requires related services such as occupational therapy. A physician’s prescription is needed to start the evaluation process.

School-based therapy is provided to give students improved access to education and is not a substitute for medically based therapy.

Fine Motor and Visual Motor Skills

Occupational therapy focuses on the development of a child’s fine motor skills and identifying visual motor deficits.

What are Fine Motor Skills and Why are They Important?

Fine motor skills are the manner in which we use our fingers, hands and arms. They include reaching, grasping, manipulating objects and using different tools like crayons and scissors.

What are Visual Motor Skills and Why are They Important?

Visual processing makes up several areas that combine what we see with what we do. We take in visual information, process it, and use it to complete motor actions. Most of the time, this collection of information and interpretation happens without us even realizing it. Visual Processing includes three main areas that impact our ability to accomplish tasks: Visual Skills (including oculomotor skills and acuity), Visual Perceptual Skills (Using visual information to understand how objects around us are related to one another and to ourselves), and Visual Motor Skills (The integration of visual information with actions in order to complete tasks). (from the OT Tool Box- https://www.theottoolbox.com/visual-motor-skills/)

Activities that require fine motor skills:

- Zipping and Buttoning

- Picking a flower

- Writing a note

- Cutting with scissors

- Turning pages of a book

- Communicating with sign language

- Brushing teeth

- Opening door

- Shaking someone’s hands

- Using an elevator

- Operation of a remote control

School-Based Speech and Language

Schools provide speech-language services when a child with a disability or delay requires this related service to help the student better access his or her education. Speech and language pathologists (SLPs) help students communicate and therapy focuses on how a student receives, acts on and shares information.

Students with speech-language delays, articulation and hearing loss, as well as, fluency disorders, voice disorders and feeding and/or swallowing difficulties may receive speech and language service in school. Areas of focus may include: Childhood Apraxia of Speech; Oral Motor Issues; Hearing Loss; Spectrum Disorders/ Pragmatics; Expressive Language / Processing Disorders; Articulation; and Neurological Disorders

Speech and Language Pathologists use focused activity to promote speech, language and communication skills, and to facilitate a child’s active participation in self-maintenance; academic and vocational pursuits; and play activities that occur in school environments.

Speech is the spoken production of language and the process through which sounds are produced. Several parts of the body work together to produce sound waves, and this motor production of speech is called articulation. The parts of the vocal tract involved with speech include the lips, tongue, teeth, throat, vocal folds, and lungs. Speech disorders affect the physical mechanisms of communication and cause problems with articulation or phonology.

Language is a system used to represent thoughts and ideas. Language is made up of several rules that explain what words mean, how to make new words, and how to put words together to form sentences. A community must share the same language in order to attach meaning to utterances. The method of delivery of language may be visual (e.g., American Sign Language), auditory (e.g., English), and/or written. Humans are the only creatures innately capable of using language to discuss an endless number of topics. Language disorders can be developmental or acquired (e.g., specific language impairment and aphasia, respectively).

Communication is the exchange of information and ideas through the use of speech and language. The transfer of information is often spoken, but may also be implied through body language or contextual cues such as intonation or hesitation. (Wikipedia)

Speech and Language Pathologists work on speech, language and communication skills. Communication skills play an important part in life’s experiences. In elementary school, children are developing language and learning to read and write. In order for a child to learn, he/she has to communicate and interact with peers and adults. Spoken language is the basis for written language. As a child grows and develops, the two types of language interact and build upon each other to improve literacy and language. This process continues throughout a person’s life. If a child has a communication disorder, they are often delayed in other areas, such as reading and math. The child may be very bright but unable to express themselves correctly, and the learning process can be affected negatively.

Speech therapy can help children learn to communicate effectively with others and learn to solve problems and make decisions independently. Communication with peers and educators is an essential part of a fulfilling educational experience. Also, children who are able to overcome communication disorders feel a great sense of pride and confidence. Children who stutter may be withdrawn socially, but with the help of therapy and improved confidence, they can enjoy a fully active social life (ASHA).

As with other therapists Speech and Language Pathologists collaborate with parents, teachers and other educational staff to help improve a student’s chance for reaching their full potential.

The school team along with the child’s family work to determine whether a child has a need for special education, and/or requires related services such as Speech and Language services. A physician’s prescription is needed to start the evaluation process.

School-based services give students improved access to education and are not a substitute for medically-based therapy.

Activities that Promote the Development of Speech and Language Skills:

- When your child starts a conversation, give your full attention whenever possible.

- Make sure that you have your child’s attention before you speak.

- Acknowledge, encourage, and praise all attempts to speak. Show that you understand the word or phrase by fulfilling the request, if appropriate.

- Pause after speaking. This gives your child a chance to continue the conversation.

- Continue to build vocabulary. Introduce a new word and offer its definition, or use it in a context that is easily understood. This may be done in an exaggerated, humorous manner. “I think I will drive the vehicle to the store. I am too tired to walk.”

- Talk about spatial relationships (first, middle, and last; right and left) and opposites (up and down; on and off).

- Offer a description or clues, and have your child identify what you are describing: “We use it to sweep the floor” (a broom). “It is cold, sweet, and good for dessert. I like strawberry” (ice cream).

- Work on forming and explaining categories. Identify the thing that does not belong in a group of similar objects: “A shoe does not belong with an apple and an orange because you can’t eat it; it is not round; it is not a fruit.”

- Help your child follow two- and three-step directions: “Go to your room, and bring me your book.”

- Encourage your child to give directions. Follow his or her directions as he or she explains how to build a tower of blocks.

- Play games with your child such as “house.” Exchange roles in the family, with your pretending to be the child. Talk about the different rooms and furnishings in the house.

- The television also can serve as a valuable tool. Talk about what the child is watching. Have him or her guess what might happen next. Talk about the characters. Are they happy or sad? Ask your child to tell you what has happened in the story. Act out a scene together, and make up a different ending.

- Take advantage of daily activities. For example, while in the kitchen, encourage your child to name the utensils needed. Discuss the foods on the menu, their color, texture, and taste. Where does the food come from? Which foods do you like? Which do you dislike? Who will clean up? Emphasize the use of prepositions by asking him or her to put the napkin on the table, in your lap, or under the spoon. Identify who the napkin belongs to: “It is my napkin.” “It is Daddy’s.” “It is John’s.”

- While shopping for groceries, discuss what you will buy, how many you need, and what you will make. Discuss the size (large or small), shape (long, round, square), and weight (heavy or light) of the packages. (ASHA)

Collaboration Between Educators, Therapists, and Families

For the student that experiences challenges in school because of a disability, delay, or injury it is essential for everyone to work together and follow through in the classroom, during the therapy session, and at home to meet the child’s educational goals.

Therapeutic Listening

CARE for Children established a pediatric therapeutic listening program with Community Innovations Funding from the United Way of the Bradford Area.

Trained therapists use sound training in combination with sensory integrative techniques to help listening become a function of the whole body, not just the ear. Hearing is a passive activity, whereas listening is active and requires the desire to communicate and the ability to focus the ear on certain sounds selected for discrimination and interpretation.

Listening skill difficulties are the inability to accurately perceive, process and respond to sounds and are often found to be an integral part of other perceptual, motor, attention and learning difficulties affecting a large number of children. Therapists use electronically altered music that has been designed to produce specific effects on listening skills when the child follows the prescribed program.

How Therapeutic Listening Can Help

Therapeutic listening may be appropriate for the child that has:

- Difficulty understanding speech in noisy situation;

- Trouble hearing in groups;

- Trouble listening;

- Becomes anxious or stressed when required to listen;

- Is easily distracted;

- Has difficulty following directions;

- Seems to hear but does not understand what people are saying;

- Has trouble remembering what people say;

- Has poor speech or language skills;

- Has poor reading or phonic skills;

- Has poor spelling skills;

- Discrepancy between verbal and performance scores and IQ tests;

- Has impulsive behavior;

- Is disorganized;

- Has poor peer relations;

- Has poor self-esteem.

The Science Behind Therapeutic Listening

In a recent study (The Effect of Sound-Based Intervention on Children with Sensory Processing Disorders and Visual-Motor Delays from the March/April 2007 edition of the American Journal of Occupational Therapy) children that participated in a therapeutic listening program showed a significant improvement on the Total Test Sensory Profile Score and significant improvement in 8 of 14 subtests that included: auditory processing, body positioning and movement, emotional responses, emotional/social responses, behavioral outcomes, multi-sensory processing and oral sensory processing. Therapeutic listening can also improve attention, social skills, self-awareness, communication skills, patterns of sleep, attention to directions and overall listening for children with sensory challenges and/or disorders.

Currently CARE has integrated therapeutic listening into its school-based occupational therapy services. The program is appropriate for children participating in other behavioral programs; children with listening deficits; and the pediatric population-at-large.

For more information about CARE’s Therapeutic Listening Program and its appropriateness for your child, please contact:

Ashley Carlson, MOT, OTR/L

Pediatric Therapy Services Director

Supervising Occupational Therapist

ashleyc@careforchildren.info